One of my most strongly held hypotheses about the world is that the US housing market is in the early stages of a slowdown that is going to last for quite a while.

This concept, of course, is not news - I don’t claim to have invented it! But I recently found some interesting data which helps support my thoughts, and as such I thought it might be interesting to walk through my thesis, talk through the drivers, and see what supporting data we can find to support the argument.

The Thesis

In the last few months, we’ve seen the Federal Reserve hike interest rates significantly, which blew cold air straight on the housing market. Sales volumes are down and prices have started to recede slightly (especially in the Western markets where they rose the most during COVID).

All of this is pretty normal stuff - what typically happens on the downslope of a business cycle. However, my thesis is that this time, things are different - the decline in sales volume and stagnation of sale prices is going to last much longer than usual. The combination of a few factors will be responsible for this:

- The massive run-up of home prices across the US, fueled by historically low interest rates and a once-in-a-generation change in work habits (work from home)

- High mortgage interest rates, a byproduct of central banks’ response to high inflation, which makes borrowing much, much more expensive for home purchases

- Zoning laws across the US continue to make it hard to build new homes where they are most needed. Even with robust housing growth across the Sunbelt, the US is not building enough homes to meet demand

Where it Leaves Us

Decreased Supply

Homes are valuable investments and people naturally don’t like (and usually can’t afford) to sell them at a loss. Many recent homeowners now own an asset which has declined, or at best held it’s value since purchase - leaving them with minimal equity, or potentially underwater on their loan.

When this happens, homeowners will usually “wait it out” rather than selling and realizing a financial loss on the home, which means that prices end up being sticky → quick to come up, and slow to come down. The result of this is fewer housing options available in the marketplace, but without much dip in sale prices.

Weakened Demand

However, should they desire to acquire a residence, potential purchasers will discover that their funds stretched considerably further in 2021 compared to 2023. I wrote an essay about this last year which I won’t belabor too much here - but suffice it to say that the monthly payment for a $750k house is much, much higher at 7% interest than 3%. Think something like $4,000 a month versus $2,600…

As such, there is going to be significantly less demand from existing homeowners to “trade up” from their starter homes into larger homes, as that would involve giving up their low interest rate and taking on a new one at much higher rates, making the total cost of the upgrade significantly more expensive.

Collective Impact: Less Liquidity

So! We have a system with both decreased supply and decreased demand, yet “sticky” prices… sounds like a perfect recipe for decreased liquidity in the market, with buyers and sellers both losing out.

Is this Escapable?

Realistically, the factor which would enable the market to “break out” of this box is a return to low interest rates. That would make purchases of expensive homes a bit more attainable, boosting aggregate demand, which would in turn slowly result in more homes being placed up for sale, thereby kick-starting the fly-wheel of future growth.

However, the Fed and other central banks seem hesitant to entertain that idea until inflation is fully settled, and even after inflation reaches a “new normal”, it’s unclear if the extremely low rate environment of the 2010s is ever something we’ll see again.

The other potential pathway out of this quagmire is on the supply side. Theoretically, developers could step in to build and sell new homes, filling the shortfall from existing homeowners “locked in” to their mortgages. The developers could elect to build more modest homes, ensuring that the purchase prices would be more moderate, even in a high interest rate environment. This would be terrific for restoring liquidity back into the housing market as a whole.

Unfortunately, America’s most desirable places to live are also the least likely to make rapid expansions in the supply of homes. Much of this is due to zoning restrictions, which mandate detached single family homes, prohibit density and verticality, and inhibit mixed-use development. Without resolving those core zoning conflicts, which would unlock the underlying value of the land by allowing it to be put to best economic use, it will be very hard to ever build enough housing in the places where it is most needed.

To that point, while there indeed is new home development popping up across the US, much of it is concentrated in the Sunbelt. While this is certainly better than nothing, it would be of significantly more economic value if that housing was being created in markets like Boston or San Francisco, where average worker productivity is higher, and where extremely high housing and commuting costs sap the potential of those cities.

Supporting Data

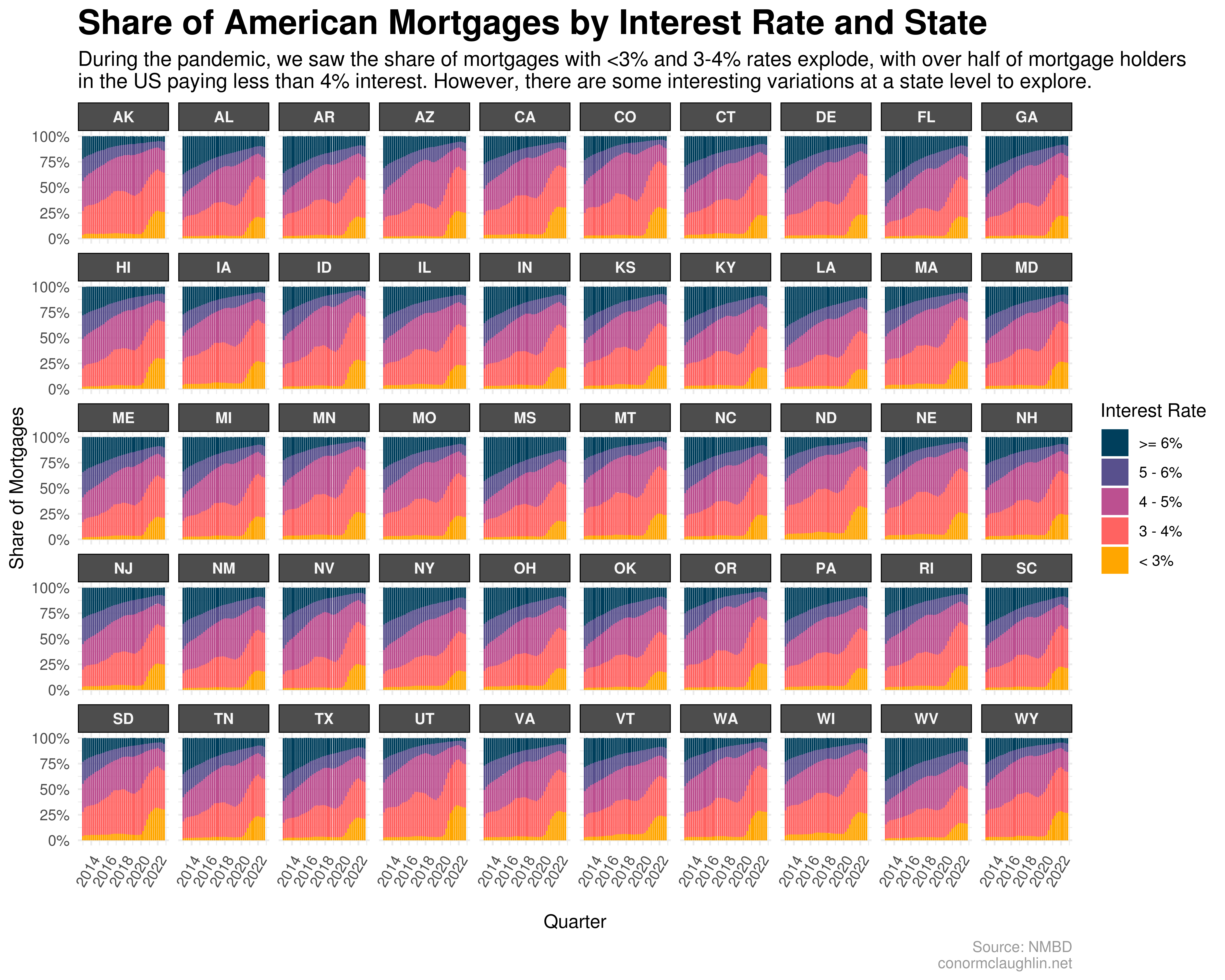

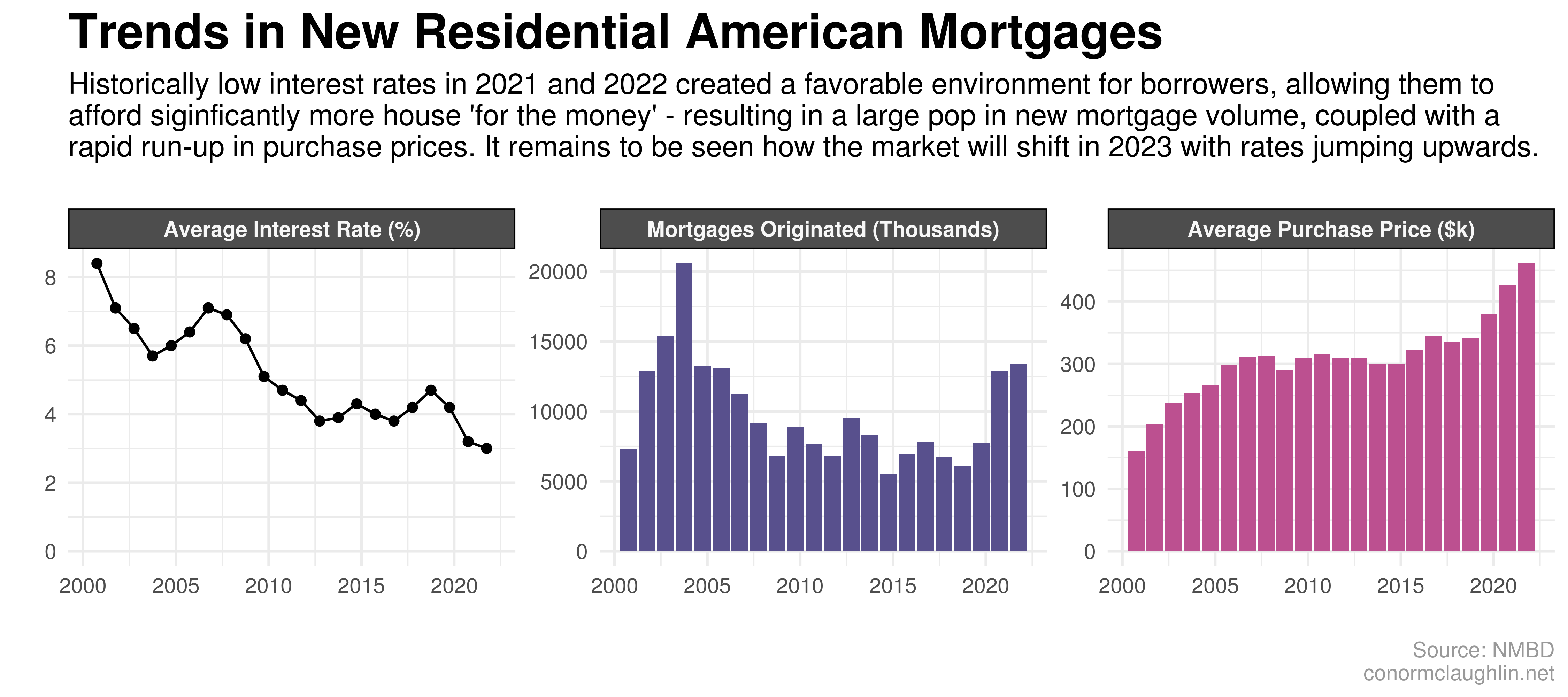

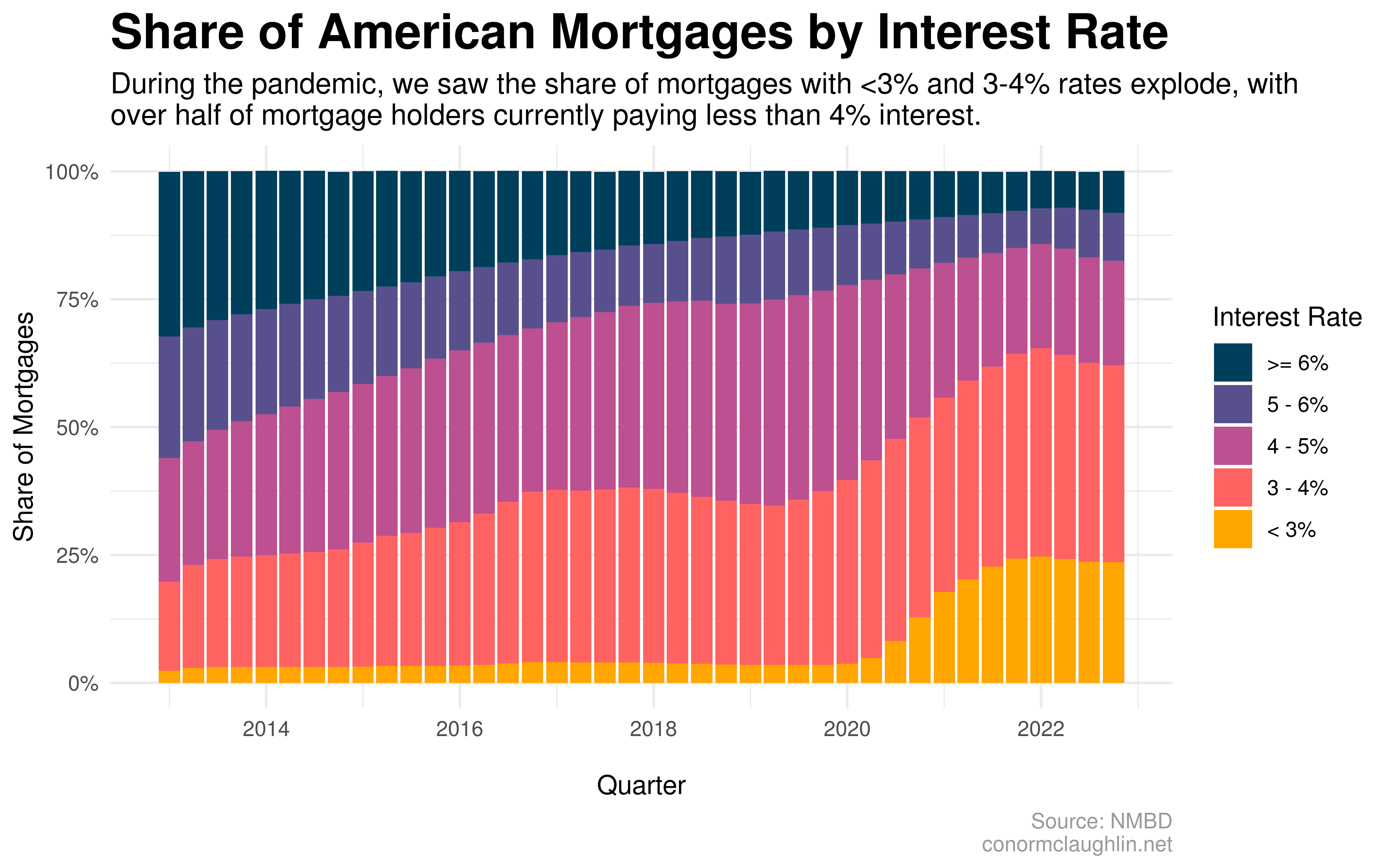

I wrote this post after spending time digging into the goldmine of data called the National Mortgage Database, a sample of 5% of residential mortgages in the US. From the NMDB data, I was able to make some really cool visuals that bolster the points I’ve made above. Take a look below, I think it’s pretty fascinating data that sheds light on just how profound the changes in the housing market over the last decade have been.

Low Rates Have Driven Higher Sale Prices, COVID Increased Purchase Volume

Monthly Mortgage Payments Climbed Significantly in Recent Years as Purchase Prices Rose

Starting in 2020, The Share of Mortgages with Low to Very Low Interest Rates Rises Significantly

With the Low Interest Rates Consistently Visible Across States